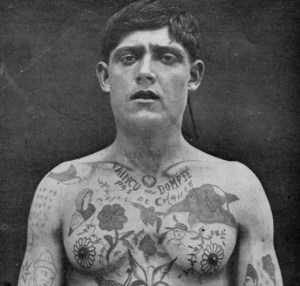

Cœur ailé et poignardé, tatoué sur la poitrine d’un récidiviste, photo du Laboratoire de police technique de Lyon, XXe siècle. Source : B.I.U. Santé.A body enhancing aesthetic practice, tattooing pertained, in the 19th century, to the world of crime and social deviance.

Cœur ailé et poignardé, tatoué sur la poitrine d’un récidiviste, photo du Laboratoire de police technique de Lyon, XXe siècle. Source : B.I.U. Santé.A body enhancing aesthetic practice, tattooing pertained, in the 19th century, to the world of crime and social deviance.

The process whereby patterns are scarred or drawn on the skin is attested as far back as the Neolithic age: the mummy of the most ancient human specimen, Ötzi, perfectly preserved in an Alpine glacier, sported 61 tattoos. A universal practice, tattooing is extant in all European and extra-European peoples. The term is derived from the Polynesian word tatau, which means, “marked on the skin” and was introduced into the English language by explorer James Cook in 1778. Originally perceived as a ‘curiosity’ worthy of the fairground freak show, tattooing, in the 19th century, extended to all classes of the European social system. Tattooed monarchs included the king of England, Edward VII, Tsar Nicholas II, along with several members of the Danish royal family. It is however in the navy, the army and the penal system that the practice was most favoured.

Tattooing was of practical use for sailors acquainted with the usage in the course of the great expeditions; it would make it possible to identify them in case of shipwreck. The famous Tichborne case in England bears out the effectiveness of the practice. In 1873, one Arthur Orton, who had sought to pass himself as sir Roger Tichborne, heir to the title and wealthy adventurer, was unmasked and sentenced for perjury for, contrary to the actual Titchborne who had gone missing at sea 20 years earlier, Orton sported no tattoos.

In the mind of later 19th century physicians and anthropologists, tattoos also represented the answer to a question that agitated European societies: How to identify a criminal at first sight? Tattoos were deemed a visible clue to a person’s nature – to their social disruptiveness. This reasoning was pioneered by the Italian physician Cesare Lombroso who operated in the 1870s in the prisons and asylums around Pavia. In 1876, he drew on his practice to publish a bestseller titled L’Uomo delinquente, in which he set forth a full range of physical signs (so-called “stigmata”) purported to typify the “criminal type” – among which tattooing. Indeed, according to Lombroso, it is this insensitivity to physical hurt alone (which he freely ascribes to criminals as well as madmen and more broadly uncivilised peoples) that makes bearable the extreme pain the process entails. The success of L’Uomo delinquente opened the way to a new scientific discipline, criminal anthropology, aimed at spotting perceptible criminal symptoms.

Lombroso was not alone in his passion for tattoos. In France, Alexandre Lacassagne, a military surgeon stationed in Algeria from 1878 to 1880 set about to trace minutely and in colours the 1333 tattoos found on men from the 2nd African infantry battalion, a so-say “disciplinary” unit absorbing hard-boiled types sentenced for desertion or other offences. In 1907, 80% of the Bataillon d’Afrique men were tattooed, regardless of official proscription. And the fascination for tattoos extended, beyond military doctors, to alienists as well. In France, Marandon de Montyel, in charge of the Seine region’s public mental asylums accordingly completed a study of their inmates’ tattoos. He, too, asserted the criminal essence of tattooing: according to him, tattooed patients were dangerous for the most part.

The political and anthropological interpretation of tattooing emerging in the 19th century, is to be read in the broader framework of analyses that closely relate a person’s physical appearance (for instance the bumps in their cranium) to their moral and psychological nature. These attempts betoken a vision of extensive classification and a mind to make visible the invisible.

Understanding tattoos as an indication of marginality and criminality rests on the practice’s social meaning. In disciplinary institutions where it is forbidden, tattooing is an affirmation of personal freedom. Effected in poor conditions with makeshift, unsterilised instruments, tattooing also proved a virility test for the person enduring the pain and risking infection. A sign of belonging to a group, tattooing essentially met social integration purposes. Besides, at a time when the art of their removal had not been mastered, tattoos were the mark of a lasting commitment: a tattooed individual (especially with facial markings) was choosing definitive social exclusion. Today widespread, tattooing no less clings to threads of its sulphurous or marginal connotations, viz respectively the Russian and Japanese mobsters or the Hell’s Angels. They may even still signify social exclusion: for instance, Japanese public bathhouses are closed to tattooed persons.

Follow the reading on the dictionary : Hymen

Références :

Philippe Artières, À fleur de peau : médecins, tatouages et tatoués, 1880-1910, Paris, éditions Allia, 2004.

Régine Plas, « Tatouages et criminalité (1880-1914) », dans Laurent Mucchielli (dir.), Histoire de la criminologie française, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1994, p. 157-167.

To quote this paper : Stéphanie Soubrier, "Tattoos" in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2021.