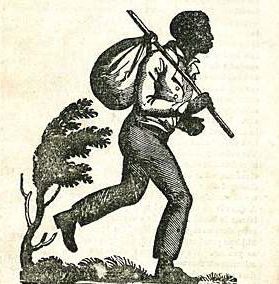

The anti-slavery record, juillet 1837.Drapotemania exemplifies the existence of psychiatric diagnoses rooted in the political stigmatisation of a social group.

The anti-slavery record, juillet 1837.Drapotemania exemplifies the existence of psychiatric diagnoses rooted in the political stigmatisation of a social group.

Even though the mental condition this word seeks to describe be wholly fictitious, and although it was short-lived, the study of the historical construction of drapetomania proves instructive. It shows that diagnoses may carry a patently political content.

It turns out some mental illnesses have a strange history indeed. Drapetomania was invented in 1851. As per its etymology, it refers to a “runaway slave’s madness”. A student of the father of American psychiatry, Benjamin Rush, doctor Samuel Cartwright, was, in 1858, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Louisiana in the United States Deep South. Both men saw blackness as a pathology, Cartwright specifically citing the tendency to flee the plantations that held the subjects in slavery in evidence; for why would slaves happy with their condition seek to flee? To Confederate physicians, such people had to be sick, impervious to the natural order of things.

Cartwright had seen the world and had been horrified, when in London in 1836, by Abolitionist propaganda. He returned to the United States in high dudgeon against all that contravened the good order of his world and his medical praxis, whether alternative practitioners or runaway slaves. He published an article about black slaves’ illnesses and idiosyncrasies in a widely circulated Southern journal. Neither were his attentions focussed exclusively on black slaves; free negroes fell prey, according to him to a kind of pathological “rascality” he labelled “Dysaesthesia Aethiopica”.

How could such a notion be upheld? Cartwright was the mouthpiece of his class, a class that defended an economic system relying on an enslaved workforce. The alienist set forth a specific treatment for this disorder based on soap and blood decarbonisation – over and above the whip and outdoors labour.

It must be noted, though, that, in support of his views, he upheld the fairly widespread 19th-century scientific theory of monomanias (fixations on one single object, in this instance flight) which French alienists had theorised some decades earlier (e.g. kleptomania, pyromania…) as well as that of interconnectedness between race, social status and pathology. The 18th century yielded a plethora of medical topographies founded in the linking between persons, illnesses and their direct environment. Finally, the idea that a person’s resistance to a societal structuring principle is tantamount to mental illness is integral to a number of psychiatric theories. Metzl’s study on Civil Rights black militants who, in the 60s, got systematically branded with paranoid schizophrenia carries echoes of the drapetomania myth.

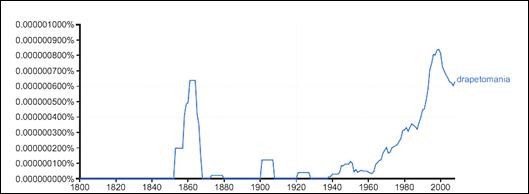

The plot, however, thickens when seeking to reconstruct the evolution of the word’s occurrences. A Google Ngram Viewer search for the word drapetomania shows that the circulation of the word in American medical circles was short-lived, some twenty years at most. Neither did it find much favour with European psychiatry. However, starting in the 60s it began a second life in a different context.

Indeed, drapetomania found a new application, not within its original psychiatric framework, but in the political denunciation by activists of the oppression of black people by their white fellow countrymen, and more pointedly of the instrumentalization of science in the process. The pathological concept, dead so close to its birth in view of its theoretical weakness and of the demise, with the War of Secession, of the economic and political system that underpinned it, was mobilised afresh. First it was called upon during the Civil Rights struggles of the 60s then even more recently following the murder of African American Michael Brown by a police officer in Ferguson in 2014.

Thus, drapetomania is one rare example of a mental illness whose second outing probably achieved a greater reach than its initial circulation in American psychiatric circles.

Références :

Katherine Bankole, Slavery and Medicine: Enslavement and Medical Practices in Antebellum Louisiana, New York: Taylor and Francis Group, 1998.

Bob Myers, "Drapetomania": Rebellion, Defiance and Free Black Insanity in the Antebellum United States, phD thesis, 2014.

To quote this paper : Hervé Guillemain, "Drapetomania" in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2021.