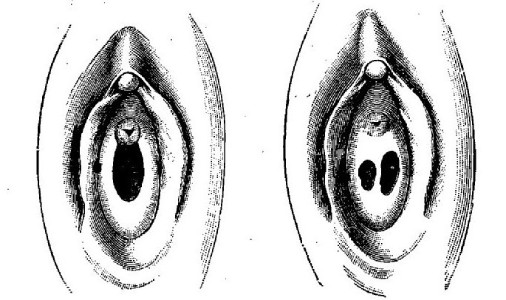

L. L. Archambault, Guide de l'examen gynécologique, 1902.By asserting the hymen, a ubiquitous trait of female anatomy, 19th physicians reinforced the taboos affecting women's sexuality.

L. L. Archambault, Guide de l'examen gynécologique, 1902.By asserting the hymen, a ubiquitous trait of female anatomy, 19th physicians reinforced the taboos affecting women's sexuality.

Despite its Greek etymology, the hymen is a novel anatomic invention; the perusal of antiquity’s great practitioners, from Aristotle (384-322 BC.) to Galen (129-201), yields no reference to a membrane partly obstructing the vaginal opening. In the Early Modern Era, medical luminaries were equally unconvinced: Ambroise Paré (ca. 1510-1590) or André Du Laurens (1558-1609) consider the hymen a fiction or a fantasy; Buffon (1707-1788) states in his Histoire naturelle that this membrane is nothing more than the invention of men who “had wanted to find in nature what dwelt only their imagination”.

However, at the turn of the 19th century, doctors assert the positive presence of a hymen in all female bodies and set it up as the guarantor of virginity: “Several anatomist have denied the existence of this membrane but it is now acknowledged that its presence is attested in all virgin girls.” Virey wrote in 1816. With a view to explain the absence of any earlier consensus, physicians argued the advances of anatomic science and the advent of a clinical anatomy founded in the detailed observation of the body. Consequently, research on the hymen proliferated: in 1840, Charles Devilliers published Nouvelles recherches sur la membrane hymen et les caroncules hyménales; several medical theses were dedicated to it. Thus did the presence of hymenal tissue become a normative attribute of virginal young women, even though a number of exceptions had to be admitted; accordingly, physicians describe the many shapes a hymen can take (annular, circular, bilabial, fringed, cribiform or even imperforate) while specifying that it may rupture without sexual intercourse – or, conversely, remain even after giving birth. Nevertheless, retaining as a specific organ what never was but a fold in the vaginal membrane, and making a norm of its presence, physicians set down a significant act, which had implications for the way virginity and defloration would be construed.

To begin with, it added to the control exerted over women’s body and sexuality since a woman’s sex life could henceforward be substantiated by anatomical features. The loss of virginity becomes a physical event that entails “breaking” the hymen, generally with attendant blood loss. Such a discourse thus offers a scientific underpinning to the social norm of female virginity, founded on the importance granted it by the Catholic Church and the archetypal bourgeois family; the physical integrity of his wife to be is, to the husband, a promise of an unsullied progeny.

The existence of the hymen as a given held good, even in the law courts; where a hymen’s condition has been known to form the basis for 19th century medico-legal experts’, finding on a husband’s impotence for annulment of marriage or divorce pleas. And overwhelmingly, the hymen was at the center of the deliberations in rape cases; in a century dominated by the pervasive suspicion of plaintiff consent, bound in the belief that a competent adult woman could always defend herself against a single aggressor, the hymen monopolised the experts’ attention. Most of 19th century major specialists, concurred to use the hymen as a key evidence of rape.

The medical validation of the hymen was carried over into popularisation books and conjugal guides, but also, more broadly, in a welter of cultural production: novels, series, pornographic films – the latter, replete with representations of bloody deflorations, contributed to anchor in the mindset the concomitance of loss of female virginity with bleeding at the first sexual intercourse. Despite scientific and/or militant reasoning to deconstruct this association, the myth is hard-wired. To wit, the presence of virginity-faking devices such as tightening creams or blood capsules to insert in the vagina – or, more recently hymenoplasty, a surgical procedure designed to recreate the membrane. This phenomenon bespeaks the ongoing significance, beyond all sexual upheavals, of normative female virginity. It is also indicative of the room for maneuver, available to women towards subverting the constraints bearing on their sexuality.

About : The project

Contribute to the dictionary : Contribute

Références :

Yvonne Knibiehler, La Virginité féminine. Mythes, fantasmes, émancipation, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2012.

Pauline Mortas, Une rose épineuse. La défloration au XIXe siècle en France, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2017.

To quote this paper : Pauline Mortas, "Hymen", in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS-EN, Le Mans Université, 2021.