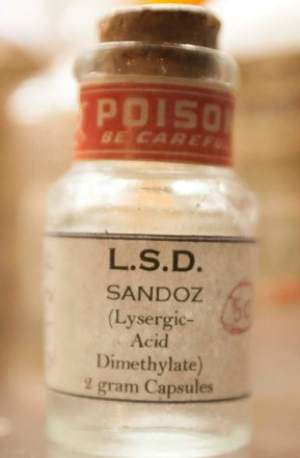

LSD from the Sandoz laboratory, 1950s-1960s, private coll.LSD was, for a while in the 50s, a promising medication before becoming controversial.

LSD from the Sandoz laboratory, 1950s-1960s, private coll.LSD was, for a while in the 50s, a promising medication before becoming controversial.

LSD25 (Lysergic acid diethylamide) is the 25th substance isolated from rye ergots, the cereal’s parasitic fungus, by the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann in 1938. Its psychotropic effects, so-called “psychedelic” (manifestation of the soul) were discovered five years later in 1943 when Hofmann accidentally consumed a small quantity of it. As of early 1947, in view of the unparalleled intensity of the psychic manifestations achieved on such a low dosage (in the order of 250 microgames), Sandoz Laboratories were sending some to psychiatrists throughout the world for them to specify its indications. In the fifties, it was one of the most studied drug in the world. Some forty major US, Canadian and European medical centres (including at least seven in France) then conducted research on LSD.

Four fields of utilisation can be distinguished for the substance. First, LSD is used for experimental purposes: some research sought a better understanding of how the brain works, notably its neurotransmitters. At the same time, it is used to refine the symptomatology of such mental illnesses as schizophrenia. It is also used for the purpose of training carers. LSD’s effects, originally described as “psychotomimetic”, that is “psychosis-simulating” were to enable them better to understand and attend to the patients’ thanks to the lived experience of temporary madness. Accordingly, most teams who worked with LSD, thus self-tested it, as was then recommended and expected by the scientific community. Finally, LSD was used as therapy; originally used in a psychiatric framework, it allowed for “accelerated” psychotherapies, thanks to its ability to elicit memories associated with an anxiolytic impact. The psychic material thus obtained enhanced the efficacity of the psychotherapy. Its antalgic powers also came into light, and it was used towards treating cluster headaches, migraines as well as in palliative care. In this last indication, the carers observed a profound change in some patients' attitude towards death: Anxiety would diminish, allowing a state of acceptation and plenitude. Lastly, it had successful outcomes in the fight against addictions, mainly heroin and alcohol abuse.

During the fifties, a section of the medical profession questioned the methodology involved in LSD-based psychotherapies. Psychiatrists and self-testers reported very positive experiences. They took place in their offices or at home, that is in comfortable, welcoming places. Conversely, their patients often gave anxiety, nay trauma-ridden accounts of their sessions conducted in the cold, impersonal context of hospital rooms. Faced with that dichotomy, some therapists sought to improve their practice and brought into question the psychiatric praxes in the process. In a new, so-called “set and setting” methodology, attention was given to the patients, their history and their account of the experience. They were informed of the substance’s effects, the room in which the session took place was decorated and they were allowed some belongings. Someone stayed with them throughout the session in a sympathetic capacity; therapists may see fit to hold hand. In traditional therapies, on the contrary, the carers’ attitude was “disciplined” distant. Patients could be tied to their bed. The subjects, often mentally ill, were put through the experience without being informed and had to submit to a set of tests.

The therapeutic outcomes varied drastically according to the methodological framework, thereby bringing the researchers involved in “set and setting” psychotherapies under suspicion; in the eyes of the rest of the scientific community, those outcomes had to come from “over-enthusiastic” types whose objectivity and scientific rigor were suspect. In fact, in the course of the sixties, LSD became more and more stigmatised as a substance hedonistically consumed and linked to the counterculture.

Gradually the taint attached to LSD splattered the researchers involved in its study. In spite of pleas for a measured response from high ranking scientists (such as Pierre Deniker in France), the weight of a popular press that had no qualms in splashing “LSD an atom bomb in the head” on its front pages influenced political actors also dealing with the times’ social unrest. In 1971, LSD was internationally prohibited. LSD is controlled as a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act. It is considered subject to “potential abuse representing a serious risk to public health while of poor therapeutic value”. All studies ceased during that decade; not before the noughties would some research teams take a fresh interest in the substance’s therapeutic possibilities.

Références :

Erika Dyck, Psychedelic Psychiatry, LSD form clinic to campus, Baltimore, The John Hopkins University Press, 2008.

Zoë Dubus, « Marginalisation, stigmatisation et abandon du LSD en médecine », Histoire, médecine et santé, N°15, 2019.

To quote this paper : Zoë Dubus, "LSD" in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2021.