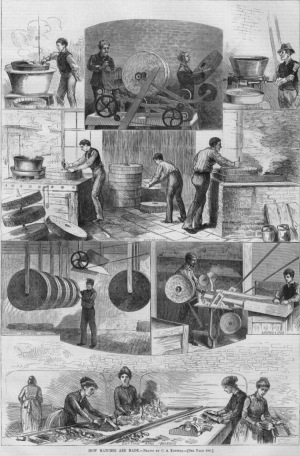

Various stages of matchmaking by C.A. Keetles. "How matches are made," Harper's Weekly, June 22, 1878, p. 488.

Various stages of matchmaking by C.A. Keetles. "How matches are made," Harper's Weekly, June 22, 1878, p. 488.

From the first decades of the 19th century up to the early 20th century, match factories exposed the thousands of men women and children working in them to a great many hazards. Anybody chopping the wood, mixing the flammable paste, dipping and drying the matches or packing them in boxes was facing several dangers. While fires and burns were ubiquitous, toxic fumes pervaded the air of the workshops.

As early as 1860, the manufacturing of matches came under investigation, some independently led by health researchers, or else, commissioned by governments. The object of many concerns, the industry was recognised as unsafe in many countries and targeted under special laws dealing with dangerous workplaces. Furthermore, the manufacturers had to countenance visits from government inspectors tasked with ensuring the proper implementation of measures aimed at the industry as well as assessing the safety of the work environment for the employees. In addition, the monitoring of the employees’ fitness to work was implemented, certifying, in principle, that no young children or workers not meeting health requirements were on site. Still, this governmental and industrial initiative was but a qualified success. Match workers still faced an employment injurious to health against a meagre salary.

The most common hazard for match workers proved to be fire, resulting in burns and respiratory inflammation. For the packers, the risk of fire injury increased because of their unceasing handling of matchsticks at a work-imposed speed, often they had only a wet sponge or a bucket of water to stop the blaze. The inspections, along with the addition of spray nozzles by employers – willing or otherwise improved the situation without solving the problem once and for all.

A number of accidents occurred in the factories – an occurrence amplified by mechanisation. In the manufacturing of matches as elsewhere, machinery became yet another hazard, especially for children. To which must be added the smoke and fumes that polluted the air in the workshops and begat many respiratory troubles and intoxications. Ubiquitous in the factory emissions of sulphur, ammonia, antimony and from a range of toxic pastes spread throughout the factory in spite of the most modern ventilation systems. Of the chemical elements affecting workers’ health, white phosphorus proved the most devastating. This inexpensive poison, used notably to kill rats, eased match ignition through friction against any rough surface. Its vapours and its ingestion caused two diseases, phosphorism and osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Observed for the first time in 1839, the impacts of this substance on the workforce are often severe destroying their health, disfiguring them, sometimes even causing the sufferer’s death. Over the following decades other health researchers looked into phosphorus impact on workers and the populace at large. What with children fainting after the ingestion of one or several match tips, some suspected matches to be the origin of some suicides, murders or even abortions.

As early as 1846, laws were passed throughout the Germanic world then in the rest of Europe and in North America to lessen the impact on men and women. Some thirty years later the wholesale ban on white phosphorus use was effected in Finland before other countries followed suite. Mostly at the turn of the century, the work of physicians, reformers and some politicians more sympathetic to the workers’ cause would help the gradual eradication of this lethal substance.

Match factories’ risk management affected their male and female workers differently whether through laws and regulation or even via inspections. With a concern for the oversight of women’s labour, several protective steps and special clauses in factory legistlation were intended to lessen their exposure to hazards. Their health, like that of children, was perceived as more fragile than that of their male co-workers. This furthered their concentration in the tasks considered less physically demanding and safer, away from wood cutters and chemical dips. For men, rotations were made compulsory in several factories in order to lessen their exposure to toxic fumes. All the same, it remains that women were in many cases over-represented among the victims of white phosphorus and that work-related injuries suffered in the course of their work were not covered in industrial law.

Read more in the dictionary : Patient associations

Read the paper in French : Allumettier.ère.s

Références :

P.W.J. Bartrip, The Home Office and the dangerous trades : regulating occupational disease in Victorian and Edwardian Britain. New York, Clio Med, 2002.

Kathleen Durocher, Pour sortir les allumettières de l’ombre : conditions de travail et de vie des allumettières de la E.B. Eddy de Hull, 1954-1929. Thèse de maîtrise, Université d’Ottawa, 2019.

To quote this paper : Kathleen Durocher, “Match workers”, in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2023.