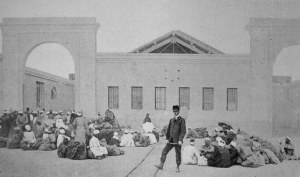

Disinfection building entrance, Lazaret de Tor.In 1865 cholera spread from Mecca to the rest of the world, redirecting just-born international health policy’s priorities on Muslim pilgrimage flows.

Disinfection building entrance, Lazaret de Tor.In 1865 cholera spread from Mecca to the rest of the world, redirecting just-born international health policy’s priorities on Muslim pilgrimage flows.

The first international health conference had taken place in 1851. In a post-1815 pacified Europe, a flourishing world trade powered by steam navigation had raised the spectre of epidemics and initiated a fresh type of diplomatic encounter that owed nothing to war. The object was for European nations to find a compromise between their need for protection against an epidemic backlash (yellow fever in 1821, cholera in 1832) and their desire to liberalize trade flows. The empirical quarantine system harking back to the Middle Ages now seemed a hindrance. In an attempt to ease it in Europe proper, it occurred to the delegates to the two first international health conferences (1851 and 1859) to remove the quarantine barrier to the Egyptian and Ottoman coastlines. In order to protect Europe, the epidemics need to be stopped where they were to be found, namely in the Near and Middle East. The Ottoman Empire was thus bid to reinforce its quarantine system and hygiene policies in the ports of departure. Consuls and physicians posted in the Ports of the Levant along with two health councils set up in Alexandria and Istanbul and partly made up with foreigners were tasked with supervising the efficacy of this barrier set on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean.

The spread of cholera from the Mecca pilgrimage in 1865, instituted a new justification to this externalisation mechanism. Thereafter, Mecca pilgrims would be considered the main “risk group” and become a major concern for Europe. The third health conference gathered in Istanbul in 1866 looked for the means to thwart this threat, linked, among other things, to the steam navigation now available to those pilgrims and which had accelerated the progress of contagion. Now the successive international health conferences of the late 19th century did not yield diplomatic agreements applicable to Europe as the elaboration of invidious international legislation floundered on national sovereignty imperatives. Each state sought to keep control of their own health policies amidst the scientific uncertainty that opposed contagionists to anti-contagionists until the advent of bacteriology at the end of the century. Conversely, based on simple “recommendations”, the pilgrimage issue brought the European powers in agreement on a hands-on approach on site. The object yet again was to protect Europe by intervening in a third-party space, namely the Red Sea where the pilgrims hailing from India, a cholera hotbed, crossed paths with other Muslim faithful.

A quarantine setup specific to Mecca pilgrim was accordingly introduced. As they reached the Red Sea, Asian pilgrims on their way to Mecca were made to stopover in a lazaret on Kamaran Island. If no cholera case emerged, they were allowed to continue on their holy journey. After the pilgrimage rituals, it was the pilgrims returning to the Muslim world’s northernmost regions, those neighbouring Europe, who were held back in a second lazaret, set in Tor near the Sinai. More secondary quarantine stations were set up along the Red Sea’s African coast and along the railway line connecting Damascus to Medina. Pilgrims were subjected to a rigorous health check and, a potentially long seclusion if incidences of cholera, then of plague when it reappeared at the end of the 19th century, were detected. Not even the migrants, another group of travellers rated dangerous, experienced such a level of control. As for “ordinary travellers”, they were no longer subject to quarantine but treated to the so-called English System, which is a health check and individual follow up which would become the norm upon the advent of bacteriology.

The special sanitary measures devised for Mecca pilgrims were imposed and controlled by the European powers. Even though Egyptian and Ottoman authorities partook in the process, they resented the loss of their sovereignty in health matters. After World War I, as the epidemic threat receded, the management of the setup was handed over to the first established international health institutions, then to the WHO as from 1948. The pilgrim’s medical regime was however considerably relaxed, notably as a result of vaccinations but the Red Sea lazarets would only disappear for good in the late 50s. At that date, the responsibility for health controls was passed on to Saudi Arabia, putting paid to over a century of international interference with the Mecca pilgrimage.

Follow the reading on the dictionnary : Excess mortality in psychiatric hospitals

Références :

Sylvia Chiffoleau, Genèse de la santé publique internationale. De la peste d’Orient à l’OMS, Ifpo/Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2012.

Saurabh Mishra, Pilgrimage, Politics and Pestilence. The Hajj from the Indian Subcontinent – 1860-1920, Oxford University Press, 2011.

To quote this paper : Sylvia Chiffoleau, "Mecca" in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2021.