La Presse, 5 juin 1989In July 1989, a handful of activists turned HIV-AIDS into a political issue.

La Presse, 5 juin 1989In July 1989, a handful of activists turned HIV-AIDS into a political issue.

From 4 to 10 July 1989, Montreal’s Palais des Congrès hosted the Fifth International Conference on HIV & AIDS. Close on 10 000 participants, including 900 journalists from 87 countries, turned up to attend several hundred scientific presentations, alongside a range of cultural events. The epidemic, which had started less than a decade earlier, was then in full swing, confronting physicians and researchers with the limits of their therapeutic powers. Which was the very substance of these yearly international gatherings, initiated in 1985 in Atlanta: take stock of the advances, but even more of the challenges, whether social, scientific or medical, brought out by this novel pandemic. The Montreal Conference, however, was different. Beyond the debates and scientific publications, it proved to be the locus for an unprecedented social mobilisation that marked a turning point in the history of the virus and of Western medicine.

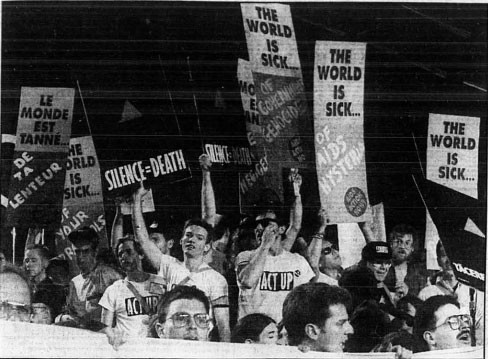

On 4 June 1989, even as Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney prepared to deliver the opening address of the Conference, between 200 and 350 demonstrators took over the platform, placards at the ready, to denounce the Federal Government’s inertia, indeed its “criminal indifference” towards the people stricken with the disease. The following day, this show-down hit the front page of all the major Canadian dailies and set the tone for the whole week. On 8 June, Professor Robert Gallo, co-discoverer of the virus with Professor Luc Montagnier, complained of the lack of time granted for scientific researchers at the conference, and deplored the excessive emphasis on the “social factor” of the illness. It was, in his view, the last great conference of its kind in terms of research. The world had indeed moved on as confirmed when, during the conference’s closing session, the speech from Quebec’s Health Minister, Thérèse Lavoie-Roux, was also heckled by demonstrators berating politicians for their inaction. “The sick’s distressed cry was to preside over the whole Conference” was the headline in Quebec’s daily La Presse on 10 June 1989.

That was just the start. The Montreal Conference would be the starting point of a movement that was to transform the history of the epidemic and more broadly the history of medicine and its relation to society. Henceforward, the patients’ voice could no longer be ignored. Act Up, Aides and other patient’s organisations continued to pressurise governments and the medical establishment in order to speed up the development of new molecules, to change the modalities of their validation and their release on the market, or to legalise condom advertising. This “patients’ revolt”, as some did not hesitate to describe it, contributed to the recognition of the word of the sick as an indispensable element of the management of care. As from the early 90s, in echo to these events, laws were passed pretty well everywhere around the world recognising the inalienable right of the sick to express their views in matters concerning their health. In France, the 4 March 2002,the “Loi Kouchner” enshrined patients’ rights in law, opening the era of so-called health democracy aimed at putting an end to the medical paternalism hitherto in force. But soon enough, upon the development of antiretroviral therapy, some protested a renewed silencing of the patients.

It remains a fact that, by bringing HIV-AIDS-related debates into the political sphere, the Montreal protesters opened a new era in the relations between medicine and the citizens, and restated the fact that health is a socio-political matter, as much as and perhaps, even before being a medical issue.

Références :

Nicolas Dodier, 2003, Leçons politiques de l’épidémie de sida, Paris, Éditions de l’EHESS.

Steven Epstein, 2001, La Grande Révolte des malades : Histoire du sida, tome 2, Paris, Les empêcheurs de penser en rond, trad. François Georges Lavacquerie.

To quote this paper : Alexandre Klein and Gabriel Girard, "Montréal - 1989" in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHis, Le Mans Université, 2021.