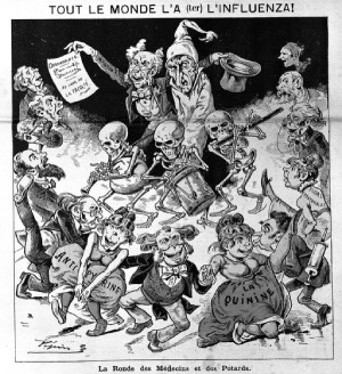

Pépin (pseudonyme de Édouard Guillaumin) “Tout le monde l'a (ter) l'Influenza [Légende : La Ronde des Médecins et des Potards.]”, Le Grelot, 12 janvier 1890 © Wellcome collection .

Pépin (pseudonyme de Édouard Guillaumin) “Tout le monde l'a (ter) l'Influenza [Légende : La Ronde des Médecins et des Potards.]”, Le Grelot, 12 janvier 1890 © Wellcome collection .

Although possibly hailing from Bukhara, in what is now Uzbekistan, it is from St Petersburg in Russia, that this “flu” spread globally. The disease has a number of names: The “St Peterburg Flu,” “Russian flu” or yet “influenza”. As it happens, we know today that its cause was not a flu virus but rather an animal sourced coronavirus. This is incidentally the first pandemic caused by a reference coronavirus.

Pandemic, the Asiatic flu swept over the world at lighting speed. As early as January 1890, within two months, the whole of Western Europe, the USA as well as Australia are infected. In the spring of 1890, Asia and Africa are contaminated in turn by the coronavirus. Africans who have never heard of the disease call it “the white man’s disease”. However, although the infectiousness is very high, the mortality rate stays low (around six out of a hundred people. It remains that the flu has caused more than one million deaths. Out of this million, one quarter are reckoned to be European deaths.

If we consider the situation in France, the disease is first observed among the staff of the Louvre department store in Paris. Out of 3900 employees, 670 were contaminated in the sole week of the 26 November 1889. From the very beginning of the winter, hospital beds were taken up by victims of the pandemic. Hospitals were overburdened as were undertakers. The disease reached its climax on 28 December when one out of ten people in Paris was sick, making it 180000 people. The disease yielded 4 to 500 dead daily and struck indifferently the military and political elites, President Émile Loubet and his ministers among them.

As happened during the Covid 19 epidemic, schools, colleges and universities were declared closed. The army was requisitioned to support a crippled postal service. The food trades such as butchers or bakers laid their staff off. But conversely the demand for information, which at the time was essentially provided by newspapers exploded. The Asiatic flu is thus the first pandemic to have made the headlines becoming in the process the first mediatic pandemic.

The pandemic context drove some to attempt to understand the way this new disease worked but also to use it to financial ends. Such were the charlatans. If scholars such as Richard Pfeiffer (1858-1945) surmised that they were in the presence of a kind of flu, there is no epistemological consensus on the matter. Yet for all that they have no idea of the microbiological origin of this disease, quacks offer remedies such as castor oil, electricity, brandy, oysters, not to mention quinin or strychnine, never mind that the latter could cause death in some cases. One treatment has remained famous to this day, namely the “Carbolic Smoke Ball”, that is a phenol inhaler whose preventive efficacy was guaranteed to the tune of £100.

This coronavirus pandemic presents other similarities with the pandemic we have recently experienced. Besides the combination of high propagation with low mortality rates (the elderly population excepted) and the closure of educational institutions, this pandemic raised societal and political questions that have a strangely familiar ring. It is worth noting the parallel between the 2020 run on chloroquine, and the shortages and speculation on quinine, the 1890s miracle drug, both prescribed to treat malaria. Similarly, multiple theories aiming to explain the origins of the disease – some verging on conspiration theory – emerged from the lower classes.

Read more in the dictionary : Livorno 1804- Barcelona 1821

Read the paper in French : Grippe russe

References :

Frédéric Vagneron, « Déchiffrer la grippe russe. Quand une pandémie devient un événement statistique (1889-1893) », Population, 2020/2-3 (Vol. 75), p. 359-389.

Frédéric Vagneron, « Une presse influenzée ? Le traitement journalistique de la pandémie de grippe « russe » à Paris (1889-1890) », Le Temps des médias, 2014, n°23, p. 78-95.

To quote this paper : Thomas Cochard, “1889-1890 pandemic”, in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2024.