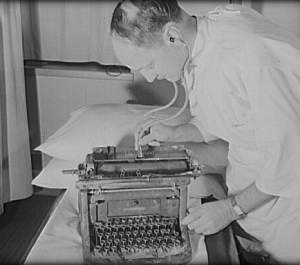

Farm Security Administration/Office of War InformationThe Covid-19 pandemic finds us revisiting an ancient practice: telemedicine.

Farm Security Administration/Office of War InformationThe Covid-19 pandemic finds us revisiting an ancient practice: telemedicine.

The current health crisis has created the opportunity to revive a practice deemed outdated by the turn of the 19th century: remote medical consultation. Indeed, as a way to help slow the spread of the virus, medical practitioners have recently been encouraged by health authorities to set up telemedical services, in other words to address their patients’ needs remotely by means of contemporary technologies. Today perceived as a minor revolution, this is nevertheless a time-honoured practice. Looking back, we can trace the practice of telemedicine to high antiquity. Galen, in the 2nd century AD, provided epistolary consultation for sufferers of ocular disorders who lived too far away to pay him a visit. While medicine by letters was a common medical convention in Bologna during the 13th century, according to L. Brockliss, it wasn’t practiced in France until the 16th century. Such consultations were consigned to records known as consislia. The most ancient was authored by Jean Fernel (1506-1558), mathematician, astronomer and physician. Published in 1582, it is conserved at the BNF.

Now who wrote such letters? Originally, they circulated within medical circles between colleagues asking for or providing advice. However, starting in the 17th century, a number of laymen adopted this mode of medical consultation to make direct contact with doctors. The practice grew and became widespread in the 18th century, which M. Stolberg designated as the “golden age” of lay epistolary consultation. This is evidenced by numerous European corpuses, including that of famed Swiss physician Samuel Tissot (1728-1797). From the 1820s onward the practice dwindled, and eventually became outdated as a different medical revolution unfolded.

Why would one choose to consult remotely? How could one cure remotely? Studying the correspondence of Etienne-François Geoffroy (1672-1731), an apothecary and doctor in early 18th century Paris, may help draw together the beginnings of an answer. Unlike contemporary telemedicine, which is designed to enable a medical consultation without the need to travel, consultations by mail took place mostly with patients who could have procured a face-to-face visit. They would already have consulted their regular doctor but without satisfactory results. Thus, writing to Geoffroy, a member of the Academy of Sciences and of the College of Physicians of Paris, consisted in seeking advice from a more prestigious physician as a last resort. The patient, or his kin, wrote a letter describing their ailments, the course of treatments already undertaken and urged the doctor to offer a new opinion, to which Geoffroy would have answered with his own analysis of the disease, its causes and a suggested treatment.

The impossibility in epistolary medicine – also true of telemedicine – for the physician to auscultate the patient had interesting consequences. The writing process encouraged in the sick a keen awareness of their ailment. The need for precision required by remote consultation drove the patient to introspection and close observation of their sensations and pushed them to make sense of their condition. The patient was thus fully involved in the resulting doctor-patient relationship because they had already taken on a therapeutic stance. In the 18th century many patients had a well-rounded medical culture as a result of the many consultations conducted beforehand; but that is not all. They also had expectations driven by their knowledge, which evolved into personal strategies, and this in turn impacted medical practice. Patients were wont to negotiate their treatment according to their own assumptions about their disease. The care relationship became an alliance in which both parties were interdependent, one required care, the other a stable clientele (the healthcare offer was at the time plethoric). The care relationship also had an affective component: intimacy would grow between doctor and patient through repeated epistolary consultation.

Nevertheless, as Geoffroy’s correspondence evinces, as well as that of Tissot, epistolary medicine as a remote medical practice was also vastly different from anything we are familiar with today. It was born out of distance and therefore needed take into account the time required for letters to be exchanged. Furthermore, the care relationship was not a face-to-face experience or one-to-one transaction. Illness was inclusive and many individuals intervened, both to write in the name of the sufferer (physician, relations, friends) as well as to take the letters all the way to Paris, where they rippled out in ever broader social circles.

About : The project

Contribute to the dictionary : Contribute

Références :

Marie Guais, Les consultations épistolaires du médecin parisien Etienne-François Geoffroy (1672-1731) : étude de la relation médecin-patiente, Mémoire dirigé par Nahema Hanafi, Université d’Angers, 2018.

Isabelle Robin, « La téléconsultation médicale : une pratique ancienne et délicate », France Culture, 28 avril 2020 : France culture

To quote this paper : Guais M., 2021, "Telemedicine", in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS-english, available at : http://dicopolhis.univ-lemans.fr/en/dictionary/t/telemedicine.html.