Testimony on the removal of bodies from the Tewkesbury Hospice, Argument before the Tewksbury Investigation Committee, 1883. © Internet Archive.

Testimony on the removal of bodies from the Tewkesbury Hospice, Argument before the Tewksbury Investigation Committee, 1883. © Internet Archive.

Over the centuries, doctors and surgeons have faced difficulty obtaining human cadavers for dissection. As early as 1319, apprentices stole cadavers for dissection in the city of Bologna, as did many of their colleagues, especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in present-day France, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, the United States and elsewhere. The city of Edinburgh, for example, was the scene of major body-snatching scandals, exacerbated by the trading of some of the corpses for money. British colonies such as Canada also recorded numerous grave robberies by medical students throughout the nineteenth century. In some countries, however, such as Belgium, the illicit procurement of cadavers was less blatant, probably due to the intervention of political authorities who facilitated the transfer of unclaimed bodies from hospitals to dissecting rooms.

From the eighteenth century onwards, human dissections were on the rise, particularly as a result of the gradual replacement of private training by teaching institutions that imposed a relatively standardised curriculum based on dissections, as well as wars and shifts in political regimes, which favoured a convergence between medicine and surgery. Dissections were therefore no longer practised exclusively by a small number of practitioners who gave public demonstrations on a single cadaver at a time in anatomical theatres open to a lay public. Instead, all training doctors and surgeons were now ideally expected to perform human dissections themselves, which only their colleagues were allowed to attend in venues that were closed to the wider public.

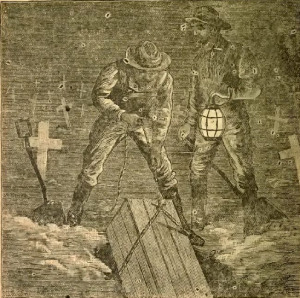

This shift in medical education promoted human dissections throughout the European empires. Having dissected a human body by oneself became one of the main criteria for distinguishing between competent practitioners and quacks in the medical circles of these empires. As it became more widespread in medical education, this incentive to dissect the dead led to a shortage of anatomical subjects resulting in more frequent body-snatching from burial grounds, which left a lasting impression on the press and literature of the nineteenth century.

The dissection of unclaimed bodies soon emerged as the remedy for body-snatching. In the history of human dissections, the tendency had always been to favour the dissection of the bodies of criminals or outsiders, in order to appease public sensibilities. British utilitarians close to the philosopher Jeremy Bentham systematised the principle of anonymity of the dissected by having it enshrined in an anatomy act in 1832, which served as a model for anatomy acts adopted in various countries.

At the heart of these nineteenth-century anatomy acts was a utility argument. Since medicine was useful to all, according to the advocates of these acts, cadavers were necessary for the education of qualified doctors. In order to achieve this aim with the least possible harm to society, the idea was to allow only the dissection of individuals who had died in state-funded institutions and who were not claimed by relatives within a period of time set by law.

By contributing to medical knowledge for the benefit of all, the unclaimed dead would thus offset the costs of their institutional care. Elected officials around the world pushed through anatomy bills based on this principle, presenting them as the only way to stop body-snatching. Thousands of unclaimed dead were thereby dissected under state supervision until the rise of body donation to science in the twentieth century.

Today, most medical schools that maintain human dissection as part of their curriculum only accept donated cadavers. Medical imaging technologies, which have been developing since the advent of X-rays in 1895, are also used to teach human anatomy, but they have not entirely replaced dissections. Respect for the dead is now the primary requirement for the use of human cadavers for medical purposes, which is reflected, among other ways, in annual ceremonies to honour the dissected in faculties of medicine, sometimes held in the presence of relatives of the deceased.

Read more in the dictionary :Zombies

Read the paper in French : Enlèvements de cadavres

Références :

Rafael Mandressi, Le Regard de l’anatomiste. Dissections et invention du corps en Occident, Seuil, 2003.

Martin Robert, « L’émeute des fémurs : contestations étudiantes, dissections humaines et professionnalisation de la médecine au Québec », Canadian Historical Review, n°102, 2021, p.525-544.

To quote this paper : Martin Robert, “Body snatching”, in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2023.