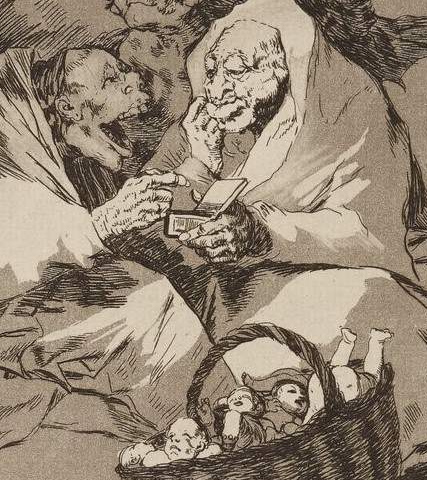

Goya, Mucho hay que chopar, 1799, GallicaIn 1852 the criminalisation of abortion is reaffirmed after the Academy of Medicine arrived at a resolution regarding therapeutic abortion.

Goya, Mucho hay que chopar, 1799, GallicaIn 1852 the criminalisation of abortion is reaffirmed after the Academy of Medicine arrived at a resolution regarding therapeutic abortion.

Why did the adjective “criminal” need adding to the word abortion at a time when this practice was firmly repressed by the Penal Code of 1810? The Penal Code, which reflects society, betrays the way the latter ended up short-changed by this move. Demography is important for it is a source of power wherefore abortion was identified as a threat, an antipatriotic crime. Furthermore, the Church denounced abortive practices, the purveyors of unbaptised infants and synonymous with the dissociation between sexuality and procreation. Thus were, in theory, all abortions criminal per se.

In 1852 the Academy of Medicine arrived at a consensus on abortion. The latter would be permitted in line with very strict conditions and criteria accounting for the conflicting rationales favouring the life of the mother or that of the child when life is endangered during pregnancy. In the event, this provision only took into account women faced with a life-threatening pregnancy, those whose pelvis was too narrow to let the baby through, those who haemorrhaged. Those whose life was not directly threatened other than in that their standing, their morality, or even their living conditions were at stake were left to their own devices, to “end their pregnancy”. Thus, an abortion which was not conducted within the accepted rules, be it conducted by a health practitioner such as a doctor, a health officer, or a midwife was outlawed.

And yet, for all that such women’s welfare was not jeopardised by their condition, their whole life was no less overturned by the arrival of an unwanted child. When a servant girl impregnated by her master found herself jobless and disgraced, the very terms of her survival were cast into doubt. The same went for the housewife providing for several children already and who saw each share dwindle on the arrival of one more. And thus it also went for the unmarried, rejected girl, the denigrated widow.

This patriotic condemnation of abortion brought an essentially masculine disapproval to bear on female bodies. It compelled women to fall back on their agency when faced with an unwanted pregnancy. For them, short of infanticide, this was a last resort for birth control, the preservation of their reputation and the protection of their living conditions. So, they turned to so called women’s secret knowledge passed from mother to daughter, and called most of the time on herbal infusions, among which a favoured combination of savin, common mugwort and rue proved potentially lethal. They also turned to persons possessed with some knowledge of female anatomy such as midwives. Alongside them, some male figures emerged who would take a part in abortion processes; men who knew what preparations can be given a pregnant woman to clear her condition – they could be herbalists – themselves the recipients of an empirical knowledge – but also men overwhelmed by their companion or lover’s condition and who resorted to extreme violence, torture, to abort them, and finally men of science who would endeavour to reinstate the menstrual flow through the ministration of emmenagogues.

Death was no stranger to the criminal abortion journey, a journey which, from the inception of abortive practices, be they herbal ingestion or other methods, took a fortnight on average. This is what emerges from the study of twenty-seven criminal prosecution records of abortion cases in Seine-et-Oise, dealing either with an abortion or an attendant crime (complicity in abortion, attempted abortion, infanticide) between 1838 and 1877 (nineteen of which were taken to the Assize Courts).

Follow the reading : Hymen

Références :

Amandine Dandel, Quand le corps des femmes était arme de crime : Traces de traitement judiciaire de l’avortement au XIXe siècle en Seine-et-Oise, Université Évry Val d’Essonne, Université Paris-Saclay, Master, Histoire Économique et Sociale, sous la direction de Nicolas Hatzfeld, 2017-2018.

Agnès Fine, « Savoirs sur le corps et procédés abortifs au XIXe siècle »,Communications. Dénatalité : l’antériorité française, 1800-1914, n° 44, 1986, p. 107-136.

Toquote this paper : Amandine DANDEL, "Criminal abortion" in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2021.