Poster by Jules-Alexandre Grün, "Doux rêve. Avoir une bicyclette Kymris", 1900.

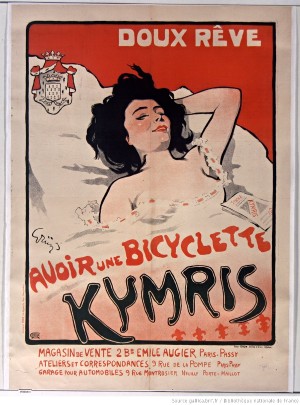

Poster by Jules-Alexandre Grün, "Doux rêve. Avoir une bicyclette Kymris", 1900.

Understood as a mental automatism, as the fulfilment of a wish or a third state of cerebral activity the phenomenon, as mundane as it is mysterious, has seemed sometimes too anarchic, sometimes too natural to defer to the influence of socio-cultural norms or political events. To be sure, major oneirologists, from Alfred Maury to Ludwig Binswanger, found a place in their works for the dreams of the distant past, but always with a view to prove the universality of their theories – that is to say the ahistoricity of dreams. The dream was granted pride of place in the history of religions by anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor at the end of the 19th century; however, his hypothesis was no more than a conjecture based not on the study of sources but on the observation of contemporary societies deemed “primitive” in other words bereft of history,

First to insist on the social and political dimensions of dreams were sociologist Roger Bastide and journalist Charlotte Beradt who studied the accounts of dreams from São Paolo African Brazilians and from Berliners oppressed by the Nazi Regime respectively. Now, not before the 1970s did the dream become a proper historical object in the pioneering works of medievalist Jacques Le Goff and the founding article by modernist Peter Burke titled “The Cultural History of Dreams”. Ever since, many studies have been dedicated to traditional and popular oneirocritical practices, to the artistic representation of dreams and to scholarly oneirologies.

Throughout the 19th century dream theories played a major part in the development of alienism and psychology in Western Europe. Then, at the turn of the century, an “oneiric revolution” as historian Yannick Ripa would have it, made of dream interpretation the key to unlocking human nature and began to spread the idea that dreams are potentially “the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious”. This watchword issued by Sigmund Freud to all the readers of his Traumdeutung has for instance instigated vast research projects on the inner life of colonial or reservations populations, and driven psychologists, sociologists, and anthropologists to collect their own oneiric experiences in the hope of fathoming single-handed the mind’s mysteries. Roger Bastide’s Sociology of the Dream and Peter Burke’s Cultural History of Dreams also fall in line with psychoanalytic hermeneutics as do other more recent propositions such as Bertrand Lahire’s Sociological Interpretation of Dreams. Indeed, all of them posit that the dream expresses in a warped way – in a “language” censored or, conversely, oblivious to all norms – intimate conflicts and desires that can only be uncovered through methodical decrypting. Even before it had conquered the realm of humanities and social sciences, psychoanalysis had instantly infiltrated cinematographic, dramatic and literary works so that it succeeded in consolidating in contemporary Western societies a new oneiro-critical culture and thereby a new way to dream, nay to self-construct as a subject.

At the end of the 1950s Nathaniel Kleitman’s team, in Chicago, and Michel Jouvet’s in Lyons effected a sea change in the history of oneirology by identifying dream as a physiological state sui generis which they named respectively “REM (rapid eye movement) sleep” and “paradoxical sleep”. The research undertaken over the following decades in the field of neurosciences challenged the psychoanalytic canon – without dethroning it in public opinion for all that – and paved the way to a biomedical approach to sleep and dreams. At the end of the 19th century, the diagnosis and therapeutic value of dreams had already been spotted as Doctors René Artigues and Philippe Tissié stressed the semiologic value of “morbid dreams” and Hippolyte Bernheim, the Nancy School of hypnosis’ mouthpiece resorted to “triggered dreams” in the framework of early “psychotherapies”; now the advent of psychoanalysis then the development of sleep medicine have come to turn those same dreams into a tool for the treatment of “nervous” disorders and a health indicator. The latter has coincidentally established that some symptoms of neurologic illnesses such as catalepsy, typical of narcolepsy or Gélineau disease and parasomnias, notably observable on patients with Parkinson's disease, are caused by the dysfunction of the systems managing paradoxical sleep and that they may to some extent be considered as “dream illnesses”.

Read more in the dictionary : Dreamcatcher

Read the paper in French : Rêve

References :

Jacqueline Carroy, Nuits savantes. Une histoire des rêves (1800-1945), EHESS, 2012.

Rebecca Lemov, Database of Dreams. The Lost Quest to Catalog Humanity, Yale University Press, 2015.

To quote this paper : Michael Roelli, "Dream" in Hervé Guillemain (dir.), DicoPolHis, Le Mans Université, 2024.