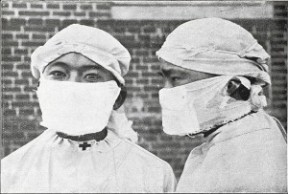

K. Chimin Wong and Wu Lien-Teh, Photograph depicting how the gauze-cotton mask should be worn, Manchurian Plague Prevention Service, 1910-1911, © Wellcome Collection.

K. Chimin Wong and Wu Lien-Teh, Photograph depicting how the gauze-cotton mask should be worn, Manchurian Plague Prevention Service, 1910-1911, © Wellcome Collection.

On 20 March 2020 Edouard Philippe’s government spokesperson, Sibeth Ndiaye, declared in an interview that she did not “know how to use a mask”, for, she asserted, wearing it required “technically precise gestures”. About one century earlier, Sino-Malayan doctor Liande Wu included the photograph illustrating this entry in a report entitled “how to wear an anti-plague mask”, resulting from field research led in Manchuria (north-eastern China) where a plague epidemic raged. Even then, those medical advocates were aware of the practicalities of mask-wearing and the specific instructions they entailed. The thematic proximity of those issues – though pertaining to distant temporalities – invites us to scrutinise the history of the mainstreaming of face masks in our globalised societies.

The 17th century plague doctor’s bird-beaked mask, a classical image frequently quoted in contemporary media, has strictly nothing to do with the realities addressed by the use of the surgical mask as we know it. The object was then to fight off supposed “miasma” (a sort of emanation, a noxious vapor) by means of products stuffed in the notorious beak. The emergence, then the affirmation of microbial theory and of bacteriology in the second half of the 19th century led to the development of new approaches towards fighting diseases, via disinfection (antisepsis) as well as protection (asepsis).

Still, the emergence of the medical mask came about following the unforeseen reconfiguration of a tool that had not been conceived to that end. The British physician Julius Jeffrey had in fact developed during the 1830s (patented in 1836) a metal and textile mesh “respirator” meant to ease the breathing of lung disease sufferers through preserving the warmth and humidity of the air breathed out by the wearer. Criticised though it was by some of his peers, Jeffrey’s invention no less gloried, included in the 1862 London universal exhibition catalogue, in one of the greatest international promotion; it thereafter travelled throughout the world as borne out by Japanese advertising of the “respirator” in the 1870s. These adverts, whether European or Japanese presented it both as a treatment tool for lung disease sufferers (its original purpose) and as the means to protect the wearer of the breathing appliance (kokyūki) from illness.

Thereafter, the emergence of plague epidemic hotbeds in Asia at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries brought on the increasingly massive use of this type of standardised protection of the nose and mouth. The onset of a plague episode in Hong Kong in 1849 and the discovery of its bacillus by Kitasato Shibasaburo et Alexandre Yersin set the trend as bacteriologists the world over began to procure respirators. But it is with the triggering of the Manchuria epidemic in 1910-1911 (and its come-back in the winter of 1921) that the first mass use of this type of equipment is observed scaled up to the health-carers in contact with the sick. It is also in the framework of the range of research produced by physicians worldwide that the term “mask” supersedes that of respirator hitherto favoured in English and in Chinese alike. It is incidentally Dr Wu Liande who proposed in his contributions to international medical forums (two symposia were held in 1911 and 1921) that the mask could be “a powerful tool to educate the Chinese people in the practice of good personal hygiene”. Wu Liande held these people (notably in north-eastern China) to be “ignorant”. This discourse, which ascribed an almost endemic nature to the disease in Manchuria, was consistent with the implicit racism of the so-called “tropical medicine” studies.

Yet, the “Spanish flu” which raged from 1917 to 1918 went global on a scale almost never seen before. The United States witnessed in this framework the inception of public policies addressing the pandemic, which brought the prophylactic mask into everyday life, notably in San Francisco, 400000 residents strong in 1910. In October 1918, the municipal authority whose public health policy was run by Dr William C. Hassler, imposed mask wearing (as per a published list) in turn to barbers, hospitality staff, shopkeepers among others. Then, after first being advised, mask wearing in public was imposed to all city residents and visitors on the 25 of the month, the mask becoming in the process “a symbol of patriotism in wartime”, as the authorities put it. The governor of California, William Stephens, echoing San Francisco’s mayor stated that mask wearing was “the patriotic duty of all American citizens”. Nevertheless the measure was suspended on 1 February 1919, in deference to San Francisco’s Anti-Mask League, as the municipality was satisfied that the public health situation had improved.

Retracing the progress of the mainstreaming of prophylactic mask wearing is thus addressing at the same time the technical, social, cultural aspects of a distinctly globalised history. Owing to 19th century conceptual medical evolutions and a reconfigured device, this mainstreaming took place against the background of brutal epidemic episodes (Manchurian plague, “Spanish flu”) which activated the development of preventive public policies against diseases.

Read more in the dictionary : Barcelona 1821

Read the paper in French : Masque sanitaire

Références :

Meng Zhang, "From respirator to Wu’s mask : the transition of personal protective equipment in the Manchurian plague", Journal of Modern Chinese History, 14:2, 2020, p.221-239.

Tomohisa Sumida, Iijima Jadie (trad.), "Covering Only the Nose and Mouth : Towards a History and Anthropology of Masks", Electronic journal of contemporary japanese studies, 21:3, 2021 (1ère éd. Jap. 2020).

To quote this paper : Clément Mei, "Face mask", in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2024.