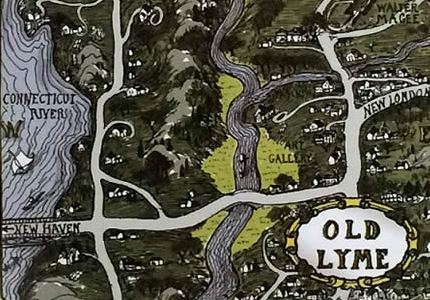

Old map of the Lyme area, United States

Old map of the Lyme area, United States

The word “Lyme” is interesting for two reasons. The first is due to the fact that the “disease” bearing this name is the object of a rather unusual dispute between, on the one hand, the “patients” who socially construct a disease in line with what they experience and, on the other, the scientists who, in their vast majority, contest the existence of such a chronic pathology. The battle lines drawn over this name are thus as political as they are medical. The second reason is due to the fact that the name by which the disease is known is not that of a physician but of a place as shown on the illustration attached to this entry. Lyme is a small town not far distant from New York where early cases of this infection are supposed to have first emerged in 1975. How do diseases get their name? Worth a study in its own right, we note in passing that diseases named after a place seem, often enough, to connote lethal danger. Think the Ebola river, the Zika forest, the city of Marburg.

Available figures show that the disease reached a turning point circa 2016. This major change must be set alongside the growing influence of patient organisations which have, over recent years pushed for the recognition of the disease. Nymphéas in 1998, Lyme éthique in 2007, France Lyme in 2008, Lyme sans frontières and Lymp’act in 2012 are as many groups whose information work is relayed by a fédération française contre les maladies vectorielles à tiques which, created in 2015, brings together physicians, researchers and patients. This federation is led by two clinician specialists in infectious diseases, Christian Perronne, author of La vérité sur la maladie de Lyme, published in 2017, and Raouf Ghozzi a keen champion of the collaboration between doctors and patients in research. The French epidemic hike reached in 2016 is thus posterior to the organising of a militant voice.

Supported by a few doctors, these patients’ policy is modelled on that adopted by the associations mobilised against HIV-AIDS. At a theoretical level, the object is to obtain, through Lyme disease, the recognition of the existence of a “bacterial AIDS”, which the authorities deny. Like in AIDS’ early days, a range of diverse accounts make up for the absence of feasible explanations for the emergence of the epidemic. A cursory glance at the story that founds the birth of the disease in the town of Lyme connects it with the nearby presence of the federal Laboratory of Plum Island, specialised in animal diseases and tasked with the fabrication of biological weapons during the Cold War. (The source for this account is Michael C. Carroll’s book, Lab 257, referred to here). The comparison with AIDS also stands in regard to militant practice. There exists, since 2013 a worldwide trend hell-bent on repudiating medical authority. In April 2019 militants from the association Le droit de guérir thus dowsed the Établissement français du sang (blood donation centre) with fake blood. In the militant documentary Lyme, la grande imitatrice, Professor Montagner, discoverer of HIV gives a long interview. The “great imitator” of the title is another disease, syphilis, the successive phases of which offered symptoms as vastly varied as those reported by Lyme patient organisations: rheumatoid, neurological, psychiatric.

For their part, physicians have a field day asserting that there is no actual disease for the very reason that the symptoms described by the patients are that diverse.

The disease reportedly goes through several phases. The first is marked by a rash around the bite that can be 15 cm wide. This is followed by a phase of bacteria dispersion leading to the last, painful phase. The passage from phase 2 to 3 is hard to determine for symptoms can remain latent for years, whereas others present rapidly. A so called “holistic” study showed that only 10% of Lyme sufferers could actually be thus diagnosed. Anybody could recognise themselves in that long list of symptoms. At that point, dialogue becomes impossible since one party’s belief and the other’s science are mutually irreconcilable. In between, the State impelled, in 2018, the adoption of a care protocol rejected by medical societies who in turn brought up new recommendations published by the Société de pathologies infectieuses in June 2019.

Beyond the polemic, the history of Lyme disease shows the extent to which the very defining and naming of diseases is a political matter, the more so with the emergence of a media-backed community activism.

Follow the reading on the dictionnary : Drapetomania - Neurodiversity

Références :

R. Lenglet et C. Perret, L’affaire de la maladie de Lyme. Une enquête, Babel 2016.

J.Y. Nau, « La maladie de Lyme, cas d'école de la rupture entre médecins et malades », Slate.fr, Juin 2019.

To quote this paper : Hervé GUILLEMAIN, "Lyme" in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2021.