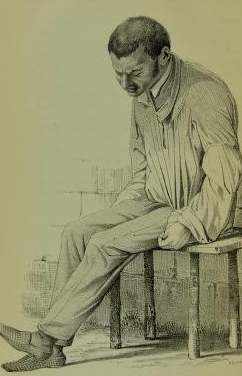

Le lypémane dans Bénédict Augustin Morel, Traité pratique et théorique des maladies mentales, 1852.The re-naming of an illness is as much a political act as a scientific one, as shown by the case of lypemania

Le lypémane dans Bénédict Augustin Morel, Traité pratique et théorique des maladies mentales, 1852.The re-naming of an illness is as much a political act as a scientific one, as shown by the case of lypemania

You say lypemania, I say melancholia… By choosing to describe his condition as lypemania, the crooner and actor Marc Lavoine unearthed for the media a mental illness vanished at the beginning of the 20th century.

It is not easy to know why a diagnosis category disappears. Even as trumpets are traditionally blown when a new illness is invented, discovered or named, no Last Post ever rings their passing away. Mental illnesses die quietly.

Leafing through French Psychiatric records one finds that lypemaniacs amounted to over a quarter of admitted patients in the 1880s. Doctor Gustave Etoc-Damazy had noted the pre-eminence of this mournful condition in his Le Mans hospital as early as the 1860s. And then, it was gone… Like the dinosaurs, it suffered a massive and brutal extinction. What kind of meteorite could have done for them?

In order to understand the disappearance of lypemania, it behoves to understand its advent. Why the invention of this word circa 1820? The etymology is cogent: being lypemaniac is being mad with sadness. The use of the suffix “mania” was appropriate since the times when the illness was named were entirely focussed on the description of deliria as mania fixated on a single object, literally monomania; it made sense to include the madness of sadness in that grouping.

Given its name by Esquirol, the lypemaniac took shape in psychiatric volumes, notably Morel’s Traité pratique et théorique des maladies mentales (1852) where his moody, whingey, withdrawn, aloof, suicidal, hallucinated image is developed. He fights the decisions that upset him, be they medical or familial. He resists dressing, eating. His relentless wailing signals his depressive drive. As for the debilitated lypemaniac, he remains motionless, mutic for hours on end his hands limp at his sides. His eyes are closed, his eyebrows furrowed, his head bent to his chest: thus do we find him in 19th century medical iconography.

Many features of this description hark back to the melancholy of old. Why not keep referring to this condition on the basis of a tried and tested concept? As Jean Starobinski reminds us in L’Encre de la folie, the object was then to complete the medicalisation of humours, sorting the more sinister, delirium-prone states, henceforth branded with the name of Lypemania on the one hand from what poetic and literary circles chose more commonly to call melancholia on the other, casting together under the same – much-abused term troubles that could be benign and not necessarily sad. Styled lypemania, medicalised melancholia thus took on, in the 19th century, a stark, depressive and demented turn.

As such, the advent of lypemania points up two political moves: the demise of a once complex understanding of melancholia and the novel practice of mental illness classification according to a new scientific order, promoted by a new discipline. Alienists, often regarded in those days as philosophers, priests – and rarely as true physicians had to singularise their vocabulary in order to establish what amounted in their view to the new science of the mind.

However, at the turn of the 20th century Lypemania breathed its last, unsung. As from the 1890s, lypemania no longer gets mentioned in Psychiatric journals. In the 1920s, not a single patient was left diagnosed under such classic 19th century psychiatric terminology.

Has sadness waned in contemporary societies or on the contrary has it become the norm? Obsessive thoughts of collapsology rather suggest that evolutions in early 20th century psychiatric classifications have much to do with this disappearance. Chronic sadness comes today under different guises, labelled with other names. Such shifts are not insignificant, however. Dementia praecox, so named by German speaking psychiatrists some years short of the 20th century, turned old melancholia into a condition the name of which left no doubt as to its tragic nature.

Read more in the dictionnary : Drapetomania- Neurodiversity-

Read the paper in french : Lypémanie

Références :

Hervé Guillemain, Schizophrènes au XXe siècle. Des effets secondaires de l’histoire, Alma, 2018.

Jean Starobinski, L’encre de la mélancolie, Paris, Seuil, 2012.

To quote this paper : Hervé GUILLEMAIN, "Lypemania" in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2021.