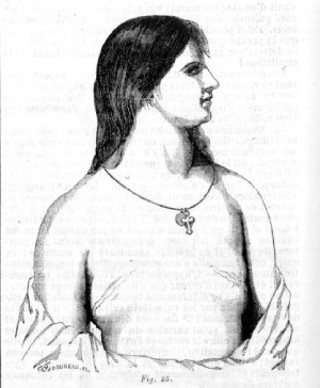

“Les Skoptzy. Cicatrices suite à l'ablation des seins”, Le progrès médical : journal de médecine, de chirurgie et de pharmacie, 1877.

“Les Skoptzy. Cicatrices suite à l'ablation des seins”, Le progrès médical : journal de médecine, de chirurgie et de pharmacie, 1877.

One of the major principles of the Skoptsy sect rests on the practice of voluntary castrations of men and women within the group. Disciples base this practice on Biblical texts from the New Testament, namely the Gospel of Matthew (18:8-9, 19:12) where eunuchs are mentioned approvingly. These religious texts were seized upon as early as 1757 by a Russian peasant, Andrei Ivanov. The founder of the Skoptsy sect, he promoted the ideal of the castrated individual standing up for some form of purity. Even though he died in Siberia upon deportation, his discourse continued to spread notably through the person of Kondrajti Selivanov. This disciple claimed to be a reincarnation of the erstwhile Tsar Peter III, but also an apostle and the son of God. The news of a eunuch messiah irked the Tsarist authority who was not amused by the use the Skoptsy made of a departed emperor’s image.

The sect preaches a life ideal resting on total abstinence, ensured by the ablation of the reproductive and pleasure-giving organs. The castration is conducted by a master of ceremony before the rest of the faithful thus consecrating the new member’s belonging to the sect. The rituals are often broken down into two stages for men, with the ablation of the testes and scrotum, followed by the removal of the penis. Though the image of the sect is strongly associated with male practices, women are also subjected to those rites via breast ablation or the resection or excision of the organs associated to sexual pleasure such as the labia majora and minora and the clitoris. In order to ensure the sect’s endurance, the faithful generally only sacrifice their organs after giving birth to two children. Castration is understood by the Skoptsy as a means of absolute abstinence, a stage towards collective redemption. It complements the sect’s ascetic practises: danse, trance, singing, dietary restraint, sexual and alcohol abstinence. Neither is castration the sole mutilation practiced by the Skoptsy whose sexual mutilations also involve burns and cuts.

Skoptsy voluntary castration pertains to religious belief, communal belonging, and collective consciousness, it is perceived as a mark of social integration. The act of adopting a castration ideal towards purification, results in facing down a society who sees those mutilations as a rupture from collective norms. Their shared conception of the body positions them as a danger, as religious fanatics. The threat is not only moral, it is also political when the Skoptsy get painted as supporting the Polish insurgents who want to overturn Russian rule. The notion of support for the Polish uprising even finds an echo in a French daily L'Indépendant des Basses-Pyrénées in 1869.

All these elements make of the Skoptsy a danger to Russian society leading to their deportation to Siberia from the sect’s very debut; such was their first leader Andreï Ivanov’s fate, then his disciple Selivanov’s too. However, in the 19th century the Tsarist authority intensifies persecutions, driving up the deportations so that between 1805 and 1870 more than 5000 Skoptsy took the road to Siberia. The authorities encourage their persecution by the Empire’s subjects through the circulation of rumours about the purchase of pauper children to be castrated. The intensification of the persecutions and deportations led to a demographic decline and migrations toward Romania.

At the beginning of the 20th century, things seemed to settle down with the 17 April 1905 Ukase, which authorised Skoptsy to leave in any city in the Empire. This soon came to an end with the onset of the Russian revolution. The counter-revolutionary power of religious sects is feared by the Bolsheviks who drive an anti-religious offensive. The Skoptsy inspire cosmopolitan alarms and pass again into clandestinity in the 1920s. They are not attacked for their absence of virility, their creepy body appearance; no, it is the political-religious dimension of their sectarian commitments that worries the Soviets. At that time, some Skoptsy seek to adjust to the Soviet model. They defend their ideals with new arguments putting forward the fact that castration helps the fight against venereal diseases and abortions. And, toning down the religious rhetoric, they also bring out the neo-Malthusian goal of castration. The Skoptsy had almost entirely disappeared by the 1930s. Voluntary castration, no longer a popular practice, is wholly reassigned to the medical field.

Read more in the dictionary : Patient associations

Read the paper in french : Secte Skoptzy

References :

Laura Engelstein, Castration and the Heavenly Kingdom: A Russian Folktale, Cornell University Press, 1999.

Élodie Serna, Les stérilisations masculines volontaires en Europe (1919-1939), Presses Universitaires Rennes, 2021.

To quote this paper : Élise Lelièvre, "Skoptsy", in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2024.