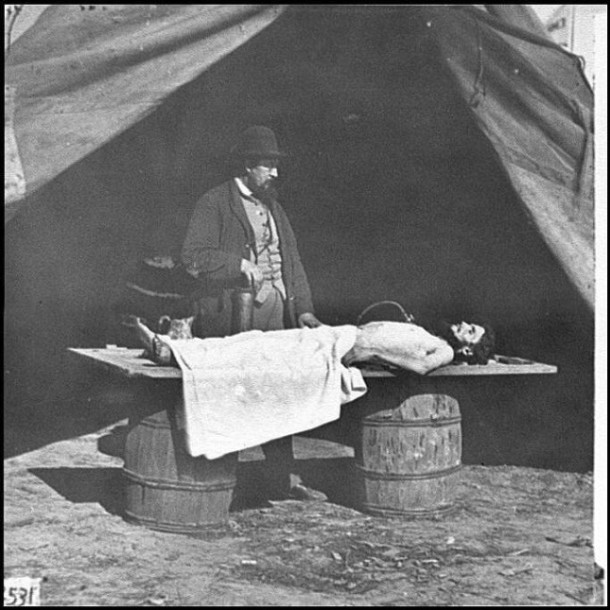

Dr. Richard Burr démontrant la procédure de l’injection artérielle sur le corps d’un soldat mort lors de la Guerre de Sécession entre 1861 et 1865. Library of Congress, Washington.

Dr. Richard Burr démontrant la procédure de l’injection artérielle sur le corps d’un soldat mort lors de la Guerre de Sécession entre 1861 et 1865. Library of Congress, Washington.

It is indeed at the end of the 18th century that Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1798-1801 Egypt expedition instigated the rediscovery of these funerary practices. In France, embalmed bodies were essentially the preserve of a minority, monarchs and princes of the blood. In the wake of the expedition that had a scientific purpose, a new clientele emerged notably among a bourgeoisie to whom mattered the representation of their departed’s body. Embalming pertains to a renewed mourning process, a demystification of death, not much in step with the times’ religious conceptions but rather with new, modern outlooks. Tanatopraxis plays a major role in the showcasing of a dead person’s image.

The embalming techniques of Ancient Egypt consisted in opening the body, flenching it and removing the viscera. The removal of the brain was achieved by means of a long hook. The hollowed cranium was filled with tar or resins. Through a cut in the flank, viscera, intestine and lungs were extracted, the hollowed abdomen was then filled with resin or bitumen. The body was then smeared with aromatic resins or saltpetre for a transitory embalming lasting several weeks or months. The temporary products were then removed and straw or moss used to restore shape to the body

Over the 18th and 19th century new methods had to be found to meet a social demand focused on the dead person’s physique. The thanatopractitioner’s task must then attend much more to the presentation of the body laid out awhile in a place allocated to family viewing. The refining of embalming techniques owes much to wars. Between the Napoleonic wars and the war of Secession, new techniques had emerged the practice of which spread across the Atlantic. In 1865, President Lincoln was embalmed. Throughout the wars, notably the Secession War (1860-1865) the business of body embalming developed whose first exponents – and first beneficiaries were the thanatopractitioners.

Jean-Nicolas Gannal’s discovery patented in 1837 did away with the mutilation of the body. His new method consisted in an arterial injection of phosphates, sodium and arsenic solutions. The thought of a plain corpse opened up then closed afresh repelled a society for whom the integrity and the beauty of the body were of primary importance and who was inclined to obfuscate the physical representations of putrefaction and death. These new 19th century embalming practices have the effect that the corpse is prepared in a symbolic and material way for its last journey. The deceased is displayed as if asleep thus associating the physical presence to the mourning process. The practice of the death mask is party to this evolution, taking a cast from the face at a person’s death was the done thing and contributed to the dead person’s posterity, see, notably, Napoleon 1st’s mask at his death in 1821.

The advent of photography brought about the practice of the ultimate portrait, of post-mortem photography which helped keep a memento of the dead person, and offer another form of posterity. These practices linked to the representation of death, along with that of the emergent individual grave bring the great embalming period to an end. This craze could represent a transition period between two funerary models that of the Ancien Régime and that of the 20th century. During the former, the body and the grave did not matter much, contrarily to the second when the tomb alone has become the main stay of the cult of the dead and of funerary art. The period when embalming was at its height thereby focussing on the deceased body marks that time of transition. This does not for all that put paid to a practice that endures. The French diploma in thanatopraxis was created in 1944 and the profession still exists though not enjoying the favour it had in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Read more in the dictionary : Criminal abortion

Read the paper in French : Embaumement

References :

Philippe Di Folco, Dictionnaire de la Mort, Larousse, coll. In Extenso, 2010.

Anne Carol, L’embaumement. Une passion romantique. France, XIXe siècle, Champ Vallon, coll. « La chose publique », 2015.

To quote this paper : Timothé Broyer, “Embalming”, in Hervé Guillemain (ed.), DicoPolHiS, Le Mans Université, 2024.